History of Camera

The history of the camera can be traced much further back than the introduction of photography. Cameras evolved from the camera obscura, and continued to change through many generations of photographic technology, including daguerreotypes, calotypes, dry plates, film, and digital cameras.

Different Types Of Camera

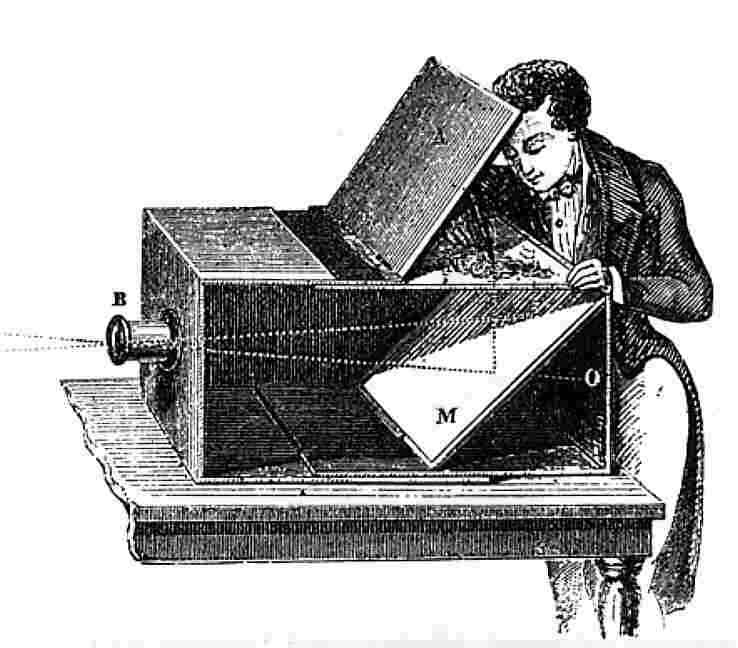

Camera obscura

An Arab physicist, Ibn al-Haytham, published his Book of Optics in 1021 AD. He created the first pinhole camera after observing how light traveled through a window shutter. Ibn al-Haytham realized that smaller holes would create sharper images. Ibn al-Haytham is also credited with inventing the first camera obscura.[4]

On 24 January 1544 mathematician and instrument maker Reiners Gemma Frisius of Leuven University used one to watch a solar eclipse, publishing a diagram of his method in De Radio Astronimica et Geometrico in the following year.[5] In 1558 Giovanni Batista della Porta was the first to recommend the method as an aid to drawing.[6]

Before the invention of photographic processes there was no way to preserve the images produced by these cameras apart from manually tracing them. The earliest cameras were room-sized, with space for one or more people inside; these gradually evolved into more and more compact models such as that by Niépce's time portable handheld cameras suitable for photography were readily available. The first camera that was small and portable enough to be practical for photography was envisioned by Johann Zahn in 1685, though it would be almost 150 years before such an application was possible.

Daguerreotypes and calotypes

After Niépce's death in 1833, his partner Louis Daguerre continued to experiment and by 1837 had created the first practical photographic process, which he named the daguerreotype and publicly unveiled in 1839.[10] Daguerre treated a silver-plated sheet of copper with iodine vapor to give it a coating of light-sensitive silver iodide. After exposure in the camera, the image was developed by mercury vapor and fixed with a strong solution of ordinary salt (sodium chloride). Henry Fox Talbot perfected a different process, the calotype,

in 1840. As commercialized, both processes used very simple cameras

consisting of two nested boxes. The rear box had a removable ground

glass screen and could slide in and out to adjust the focus. After

focusing, the ground glass was replaced with a light-tight holder

containing the sensitized plate or paper and the lens was capped. Then

the photographer opened the front cover of the holder, uncapped the

lens, and counted off as many seconds—or minutes—as the lighting

conditions seemed to require before replacing the cap and closing the

holder. Despite this mechanical simplicity, high-quality achromatic lenses were standard.

Collodion dry plates had been available since 1855, thanks to the work of Désiré van Monckhoven, but it was not until the invention of the gelatin dry plate in 1871 by Richard Leach Maddox that the wet plate process could be rivaled in quality and speed. The 1878 discovery that heat-ripening a gelatin emulsion greatly increased its sensitivity finally made so-called "instantaneous" snapshot exposures practical. For the first time, a tripod or other support was no longer an absolute necessity. With daylight and a fast plate or film, a small camera could be hand-held while taking the picture. The ranks of amateur photographers swelled and informal "candid" portraits became popular. There was a proliferation of camera designs, from single- and twin-lens reflexes to large and bulky field cameras, simple box cameras, and even "detective cameras" disguised as pocket watches, hats, or other objects.

The short exposure times that made candid photography possible also necessitated another innovation, the mechanical shutter. The very first shutters were separate accessories, though built-in shutters were common by the end of the 19th century.[11]

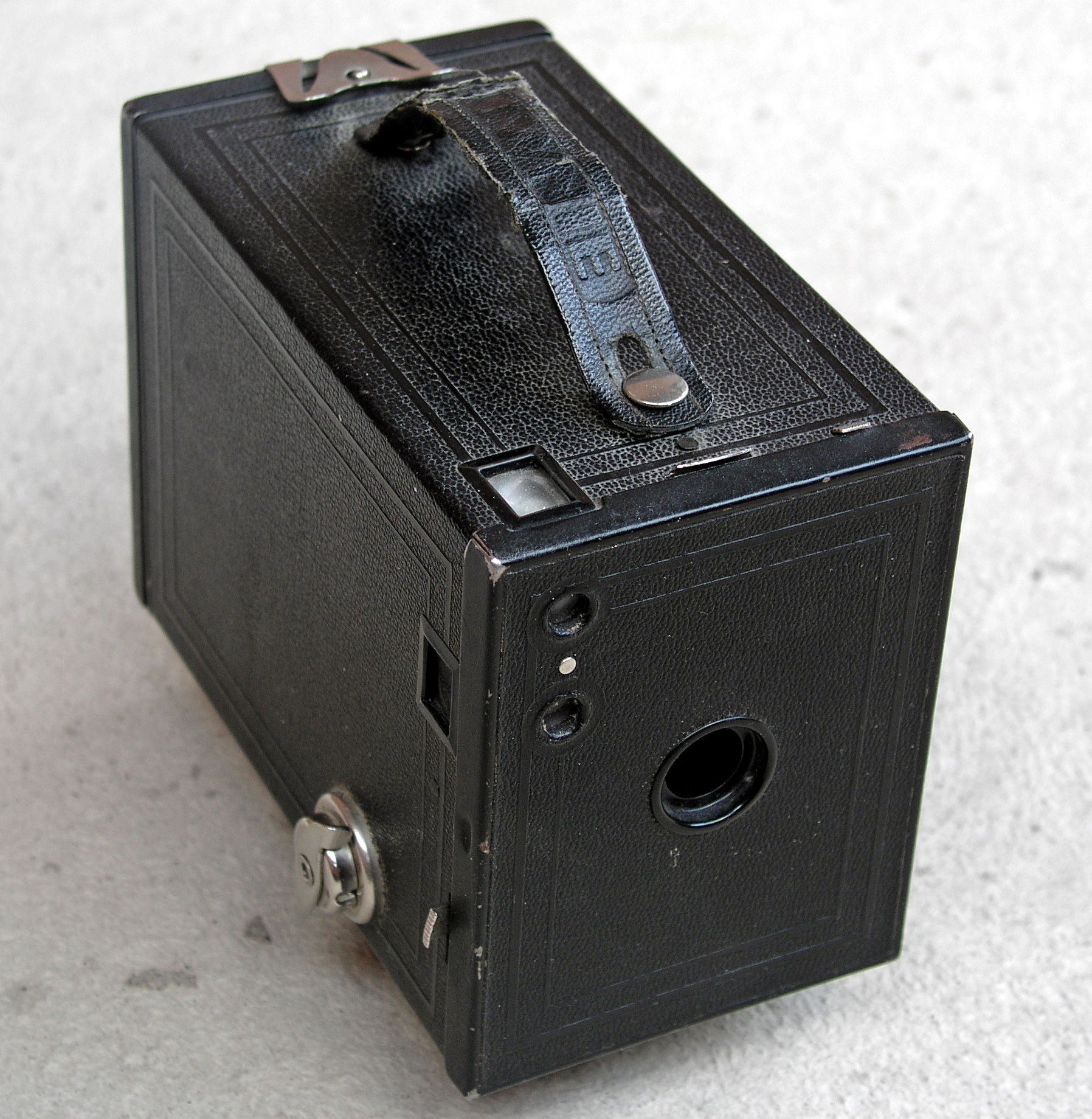

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first camera, which he called the "Kodak," was first offered for sale in 1888. It was a very simple box camera

with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its

relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came

pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back

to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished.

By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to

several models including both box and folding cameras.

In 1900, Eastman took mass-market photography one step further with the Brownie, a simple and very inexpensive box camera that introduced the concept of the snapshot. The Brownie was extremely popular and various models remained on sale until the 1960s.

Film also allowed the movie camera to develop from an expensive toy to a practical commercial tool.

Despite the advances in low-cost photography made possible by Eastman, plate cameras still offered higher-quality prints and remained popular well into the 20th century. To compete with rollfilm cameras, which offered a larger number of exposures per loading, many inexpensive plate cameras from this era were equipped with magazines to hold several plates at once. Special backs for plate cameras allowing them to use film packs or rollfilm were also available, as were backs that enabled rollfilm cameras to use plates.

Except for a few special types such as Schmidt cameras, most professional astrographs continued to use plates until the end of the 20th century when electronic photography replaced them.

In 1900, Eastman took mass-market photography one step further with the Brownie, a simple and very inexpensive box camera that introduced the concept of the snapshot. The Brownie was extremely popular and various models remained on sale until the 1960s.

Film also allowed the movie camera to develop from an expensive toy to a practical commercial tool.

Despite the advances in low-cost photography made possible by Eastman, plate cameras still offered higher-quality prints and remained popular well into the 20th century. To compete with rollfilm cameras, which offered a larger number of exposures per loading, many inexpensive plate cameras from this era were equipped with magazines to hold several plates at once. Special backs for plate cameras allowing them to use film packs or rollfilm were also available, as were backs that enabled rollfilm cameras to use plates.

Except for a few special types such as Schmidt cameras, most professional astrographs continued to use plates until the end of the 20th century when electronic photography replaced them.

33 mm

A number of manufacturers started to use 35mm film for still

photography between 1905 and 1913. The first 35mm cameras available to

the public, and reaching significant numbers in sales were the Tourist

Multiple, in 1913, and the Simplex, in 1914.[citation needed]Oskar Barnack, who was in charge of research and development at Leitz, decided to investigate using 35 mm cine film for still cameras while attempting to build a compact camera capable of making high-quality enlargements. He built his prototype 35 mm camera (Ur-Leica) around 1913, though further development was delayed for several years by World War I. It wasn't until after World War I that Leica commercialized their first 35mm Cameras. Leitz test-marketed the design between 1923 and 1924, receiving enough positive feedback that the camera was put into production as the Leica I (for Leitz camera) in 1925. The Leica's immediate popularity spawned a number of competitors, most notably the Contax (introduced in 1932), and cemented the position of 35 mm as the format of choice for high-end compact cameras.

Kodak got into the market with the Retina I in 1934, which introduced the 135 cartridge used in all modern 35 mm cameras. Although the Retina was comparatively inexpensive, 35 mm cameras were still out of reach for most people and rollfilm remained the format of choice for mass-market cameras. This changed in 1936 with the introduction of the inexpensive Argus A and to an even greater extent in 1939 with the arrival of the immensely popular Argus C3. Although the cheapest cameras still used rollfilm, 35 mm film had come to dominate the market by the time the C3 was discontinued in 1966.

The fledgling Japanese camera industry began to take off in 1936 with the Canon 35 mm rangefinder, an improved version of the 1933 Kwanon prototype. Japanese cameras would begin to become popular in the West after Korean War veterans and soldiers stationed in Japan brought them back to the United States and elsewhere.

TLRs and SLRs

The first practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR

of 1928. Though both single- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been

available for decades, they were too bulky to achieve much popularity.

The Rolleiflex, however, was sufficiently compact to achieve widespread

popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both

high- and low-end cameras.A similar revolution in SLR design began in 1933 with the introduction of the Ihagee Exakta, a compact SLR which used 127 rollfilm. This was followed three years later by the first Western SLR to use 135 film, the Kine Exakta (World's first true 35mm SLR was Soviet "Sport" camera, marketed several months before Kine Exakta, though "Sport" used its own film cartridge). The 35mm SLR design gained immediate popularity and there was an explosion of new models and innovative features after World War II. There were also a few 35mm TLRs, the best-known of which was the Contaflex of 1935, but for the most part these met with little success.

The first major post-war SLR innovation was the eye-level viewfinder, which first appeared on the Hungarian Duflex in 1947 and was refined in 1948 with the Contax S, the first camera to use a pentaprism. Prior to this, all SLRs were equipped with waist-level focusing screens. The Duflex was also the first SLR with an instant-return mirror, which prevented the viewfinder from being blacked out after each exposure. This same time period also saw the introduction of the Hasselblad 1600F, which set the standard for medium format SLRs for decades.

In 1952 the Asahi Optical Company (which later became well known for its Pentax cameras) introduced the first Japanese SLR using 135 film, the Asahiflex. Several other Japanese camera makers also entered the SLR market in the 1950s, including Canon, Yashica, and Nikon. Nikon's entry, the Nikon F, had a full line of interchangeable components and accessories and is generally regarded as the first Japanese system camera. It was the F, along with the earlier S series of rangefinder cameras, that helped establish Nikon's reputation as a maker of professional-quality equipment.

Instant cameras

While conventional cameras were becoming more refined and sophisticated, an entirely new type of camera appeared on the market in 1948. This was the Polaroid Model 95, the world's first viable instant-picture camera. Known as a Land Camera after its inventor, Edwin Land, the Model 95 used a patented chemical process to produce finished positive prints from the exposed negatives in under a minute. The Land Camera caught on despite its relatively high price and the Polaroid lineup had expanded to dozens of models by the 1960s. The first Polaroid camera aimed at the popular market, the Model 20 Swinger of 1965, was a huge success and remains one of the top-selling cameras of all time.

Automation

The first camera to feature automatic exposure was the selenium light meter-equipped,

fully automatic Super Kodak Six-20 pack of 1938, but its extremely high

price (for the time) of $225 ($3770 in present terms[12])

kept it from achieving any degree of success. By the 1960s, however,

low-cost electronic components were commonplace and cameras equipped

with light meters and

automatic exposure systems became increasingly

widespread.

The next technological advance came in 1960, when the German Mec 16 SB subminiature became the first camera to place the light meter behind the lens for more accurate metering. However, through-the-lens

metering ultimately became a feature more commonly found on SLRs than

other types of camera; the first SLR equipped with a TTL system was the Topcon RE Super of 1962.

Digital cameras

Digital cameras differ from their analog predecessors primarily in that they do not use film, but capture and save photographs on digital memory cards or internal storage instead. Their low operating costs have relegated chemical cameras to niche markets. Digital cameras now include wireless communication capabilities (for example Wi-Fi or Bluetooth) to transfer, print or share photos, and are commonly found on mobile phones.

Image Source

Walang komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento